The Library of Montecassino: A Thousand-Year History

From Archive to Library

For centuries at Montecassino, the library and the archive shared the same space. Documents and manuscripts were kept together under the care of a monk who, as Pietro Diacono recalls, served simultaneously as cartularius, scriniarius, and bibliothecarius. Only from the early 16th century were manuscripts and printed books separated from archival documents; by the late 18th century, printed books were also separated from manuscripts, which were reunited with the archival collection.

Abbot Desiderius and the “parva edecula”

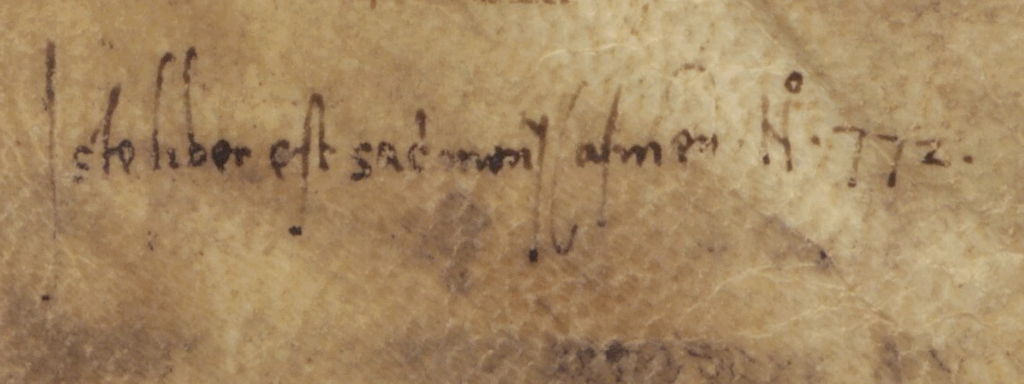

It was Abbot Desiderius (1058–1087), during the great restructuring of the abbey, who wanted a space devoted to books: a parvula edecula, next to the chapter hall and the main church, as reported by Leo of Ostia. From the 16th century onward, manuscripts and early printed editions were housed here together. In 1504, the archive was reorganized, and from that time, a note of ownership in cursive humanistic script began to appear on manuscripts and printed books: «Iste liber est sacri monasterii Casinensis n.°».

Books on the Move

Some incunabula bearing Montecassino’s ownership marks are now far from the abbey. In Naples, at the National Library, there is a copy of Saint Thomas’s Opuscula (Venice, 1498) with multiple ownership formulas from Montecassino and from the convent of Santa Brigida in Posillipo. In Rome, at the National Central Library, there is a copy of Gregory I’s Moralia (Brescia, 1498); in Mantua, Giovanni da San Gimignano’s Liber de exemplis (1499); and in Subiaco, Saint Vincent Ferrer’s Sermons (1496). The details of these dispersals still remain to be investigated.

Chains, Papal Bulls, and Curses

Until the early 16th century, the librarian was responsible for both books and documents – a fact demonstrated by the catalogue preserved in Vat. lat. 3961, which lists important public documents immediately after the books. By 1575, the library was located between the chapter hall and the “fire room.” Here, as Placido Petrucci recounts, the volumes were chained to lecterns. In 1588, Pope Sixtus V issued the bull Regularium personarum, threatening excommunication to anyone who removed books or manuscripts without permission – an edict that, until the Second World War, was likely displayed in the library. The French monk Simon-Germain Millet, visiting in 1605, also noted the chains and described the library in detail.

Perhaps originally protected by chaining them to the lecterns like the manuscripts, most of the incunabula we see today have undergone the removal of their original bindings; therefore, it is not possible to ascertain the existence, even in potential traces, of this method of protection. It should be noted that, perhaps as an additional safeguard, one incunabulum in the Montecassino collection contains the opening portion of an anathema—a formula used especially in medieval manuscripts to ward off theft. This is the incunabulum with the current shelfmark P-VII-8, the Speculum historiale by Vincent de Beauvais, printed in Venice in 1494 by Hermann Liechtenstein, which bears the incomplete formula: Si quis hunc furto rapiat libellum (16th century; fol. IIr). On the following leaf, the volume also carries Montecassino’s typical ownership notes: Est sacri monasterii Casinensis […] and Publicae Bibliothecae Casinensi deputatus.

New Shelves and Bindings

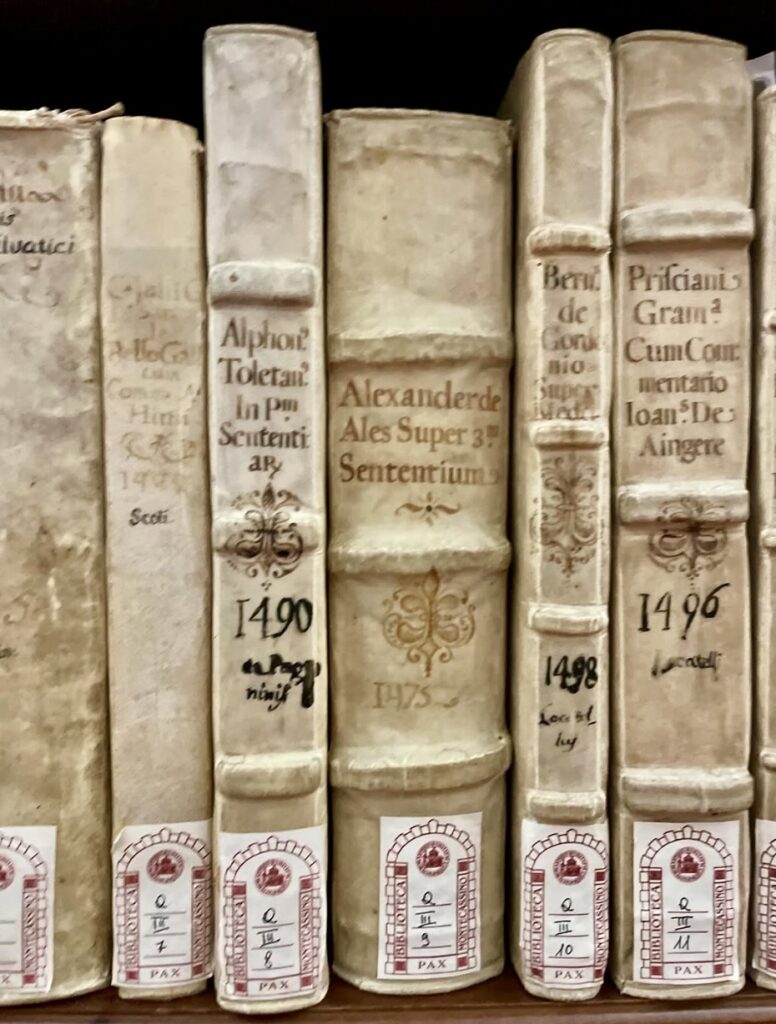

As late as 1636, the volumes were still chained. Another distinguished visitor, the Maurist scholar Jean Mabillon, came to Montecassino in November 1685 and expressed great admiration for the library and archive. This was during the tenure of Abbot Sebastiano Biancardi of Milan (1681-1687), who had overseen the rebinding of manuscripts and printed books and commissioned new shelving for the library. All the original covers of the incunabula were replaced with rigid parchment bindings, raised bands, and handwritten bibliographic data on the spines, often with decorative flourishes. This extensive rebinding formed part of a broader reorganization that gave the collection a unified appearance – Mabillon himself noted that the books were “libri omnes de novo eadem forma operti.”

The shelving was rebuilt and the library reorganized. Additional restorations and rebindings took place over the following centuries, continuing into the 21st.

Growth and Catalogues

The library grew significantly in the 17th and 18th centuries thanks to acquisitions made under Abbots Andrea Deodati (1687–1693) and Arcangelo Brancaccio (1722–1725), as well as through the initiatives of Abbots Giustino and Antonio Capece in the mid-18th century. Many books were also bequeathed by monks upon their death. In 1763, Don Placido Federici was tasked with compiling a new library catalogue, completed within a year: two in-folio volumes describing the library’s entire holdings.

Destruction and Renewal

Of the monumental late-17th-century library destroyed in the 1944 bombing, nothing remains but the still-unpublished account by Don Erasmo Gattola, librarian from 1686 and archivist from 1697. He described books arranged in beneaptati loculi and cupboards crowned with sculptures of saints such as Gregory the Great, Anselm, Peter Damian, Bernard of Clairvaux, Rabanus Maurus, and Cassiodorus. Gattola worked to expand the library through personal donations and to repair damaged volumes.

Under the 1807 law suppressing religious orders, Montecassino retained its library and archive—recognized, along with those of Cava and Montevergine, as integral to its historical identity. Custody was entrusted to a director and fifty monks charged with arranging the books and promoting works relevant to the history of the Kingdom.

A second suppression came with Italian unification: the laws of 7 July 1866 (no. 3096) and 15 August 1867 (no. 3848) ordered the confiscation of all monastic assets. For Montecassino, designated a “national monument,” the State undertook to preserve the buildings and their archival, bibliographic, artistic, and scientific heritage.

The abbey was destroyed in 1944. In the autumn of 1943, the library and archive materials had already been packed into hundreds of wooden crates marked MC. BIBL. or MC. PRIV. , containing respectively the Monumental Library and the Private Library collections. Alongside them were codices, liturgical books, items from the 16th- and 17th-century pharmacy, and other valuable volumes. Transported by the German military, the materials were first taken to Colle Ferreto near Spoleto – where they were inspected by Friedrich Wilhelm Deichmann—and then to Rome on 8 December 1943.

Deposited at Castel Sant’Angelo and later in the Vatican, the crates were recorded in multiple official reports, signed by Don Anselmo M. Albareda and various government officials. In February and March 1944, additional crates arrived in the Vatican containing charters, parchments, choir books, and volumes from the private library.

In 1947, the collection was moved to the Benedictine Abbey of San Girolamo in Rome, where it remained until 1955, when it was definitively returned to Montecassino—a transfer documented in the chronicle of Don Angelo Pantoni and in a detailed report by Michele Pardo of the Central State Archive.

The Library Today

Today, the library occupies an entire wing of the rebuilt abbey, with separate spaces for historical and modern materials. The historical holdings comprise the Monumental Library and the Private Library, now named the “Paolo Diacono” Monastic Library. In addition to traditional printed catalogues, the historical collections are listed in the OPAC SBN. The incunabula collection is also described in the volume Incunaboli a Montecassino, edited by Francesca Aiello, Corrado Di Mauro, Debora Di Pietro, Simona Inserra, Marco Lugnan, Marco Palma, and Laura Rogari (Viella, 2025); provenance data for all incunabula are recorded in MEI (Material Evidence in Incunabula).