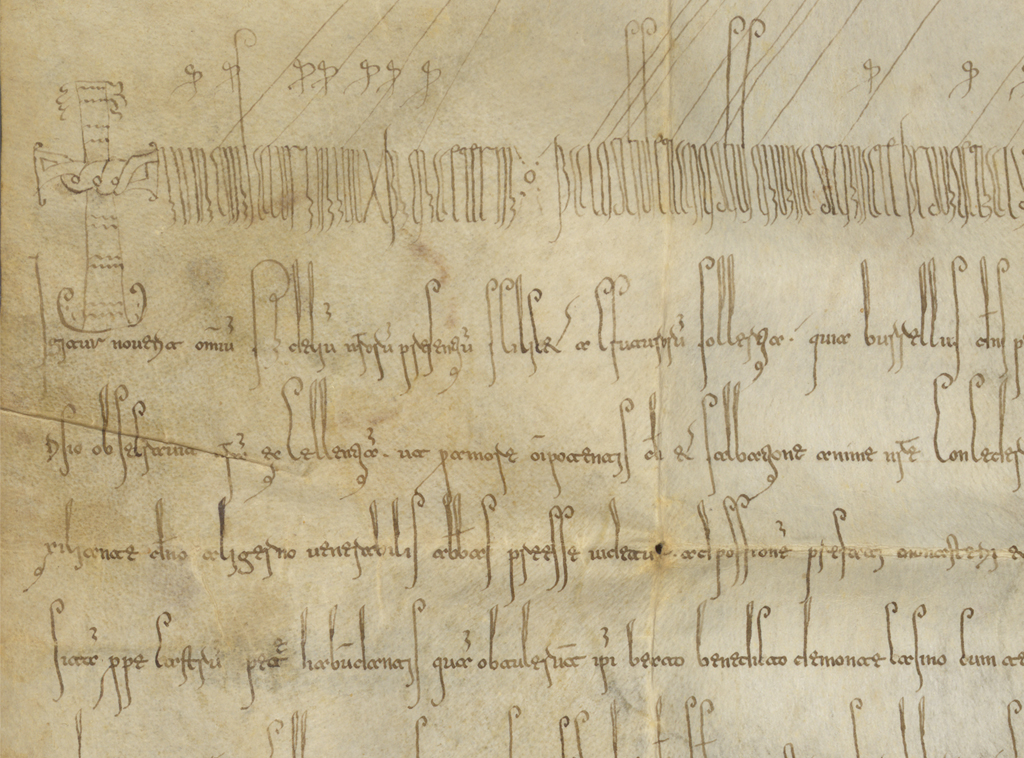

The roots of the Abbey of Montecassino run deep through written records

Paul Fridolin Kehr once described the Montecassino archive as “a true diplomatic repository, rivaled by only a few archives in the world.” But the archive is more than that: it has been one with the Abbey, breathing with it, following its every step, bearing witness to its religious, cultural, political, and institutional life, and to the people who lived there or had dealings with it. Like every archive, it has followed its own rhythm: expanding in times of growth and splendor, contracting during crises—fires, sieges by Lombards and Saracens, earthquakes like the one in 1349, and finally the devastating bombing of 1944 that razed the Abbey and forced the monks once more into exile. Yet always, after every exile, the monks returned home; always, after every destruction, the archive’s breath returned to normal.

For centuries, the archive and the library lived with each other, for each other, and within each other. In the mid-12th century, Peter the Deacon described himself as bibliothecarius, cartularius and scriniarius a trusted and capable custodian of both books and documents, responsible for the scrinia from which the Abbey drew its lifeblood and which safeguarded the munitiones necessary for its spiritual and material survival. But already in the 1200s, when Abbot Aiglerio was writing his commentary on the Rule of Saint Benedict, the person responsible for the preservation of the chartae, the instrumenta and the privilegia seems to have been distinct from the person assigned to the library, who was entrusted with the book collection alone: although in actual fact, the distinction between the space of the archive and that of the library, as well as the distinction between the figure of the archivist and that of the librarian, may not have been so clear-cut. Indeed, in the Introduction to the first volume of his justly celebrated Regesti of the Archive, speaking of the monks who most influenced the formation, the transformations, and the organization of the Cassinese archive, Dom Tommaso Leccisotti recalls that even in the year 1500 there existed a dual-role figure, bibliothecarius et custos archivii, responsible in equal measure for codices and documents, which were moreover kept in a single space corresponding to the parvula edecula established centuries earlier by Abbot Desiderius in the eastern area of the monastery, toward the church. At the end of the 1500s, however, as Dom Placido Petrucci recounts in his Chronicle, a new location was found for the documents, still within the same eastern wing, but near the cemetery oratory of Saint Anne.

It is possible that the new arrangement was connected to the incorporation of Montecassino in 1504 into the already existing Congregation of Santa Giustina of Padua, following which the Congregation itself took the name “Cassinese.” After this unification, in fact, the so-called Cassinese State, or State of San Germano, began to deposit in the archive of the Abbey the records of its own administration, causing the documentation preserved in the Abbey to increase exponentially in both quantity and variety. Inevitably, it was then that the need arose for an organic and systematic reordering of the archival material, which was initially carried out by d. Antonio Petronio, who produced for the Abbey a first Repertorio (Repertory) that, however, has not come down to us, and then by the already mentioned d. Placido Petrucci who, in addition to compiling a still very useful inventory of the parchments preserved in the sacculi, described with accuracy in the Descriptio Sacri Monasterii Casinensis, included in his Cronaca, the rooms that in the 16th century pertained to the archive.

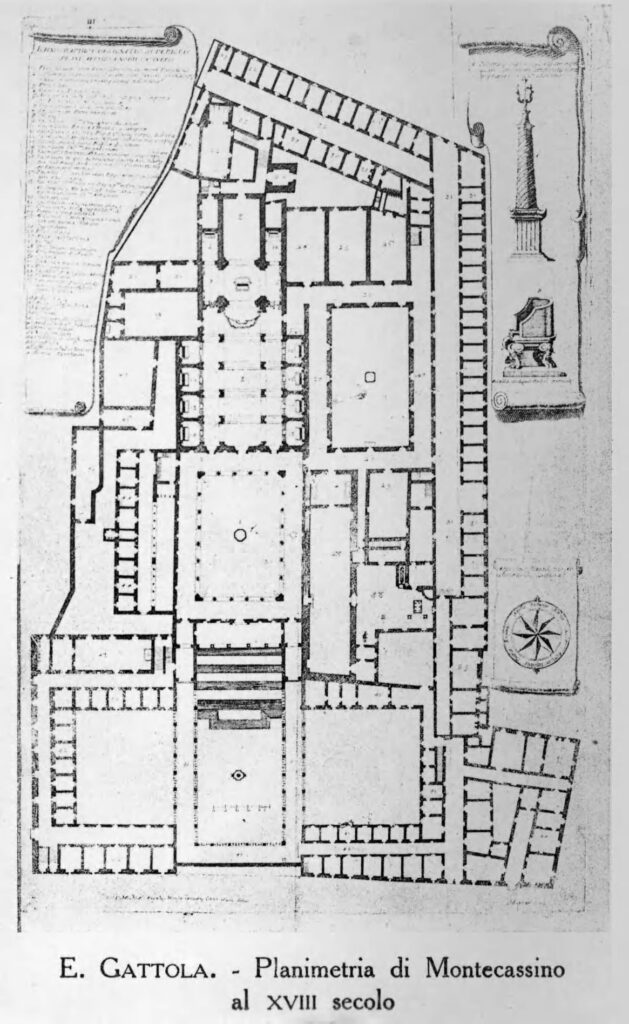

Many were the learned monks who succeeded one another in the custody of the archive and the library: among them a special place is certainly occupied by d. Erasmo Gattola, who directed the archive from 1697 until his death in 1734 and gave it its definitive form. With his Historia Abbatiae Cassinensis per saeculorum seriem distributa, imbued with the newest principles of documentary criticism learned thanks to his contact with the Maurist Jean Mabillon, Gattola for the first time in a certain sense opened the archive to the public, allowing anyone interested in Cassinese history indirect but broad access to critically examined documentary sources. It was also with d. Gattola that the series of the Giornali, which since the foundation of the Cassinese Congregation had the purpose of fixing almost daily the memory of the events and affairs concerning the Abbey, acquired particular prominence and systematicity, so that from that moment it is possible to reconstruct in detail and with good precision the life of the archive, despite some gaps caused by historical events that marked the life of Montecassino.

The events following the prefecture of d. Gattola are well known thanks to the introductory chapters of the eleven volumes of the Regesti dell’Archivio by d. Tommaso Leccisotti. But the recent history of the Cassinese archive unfolds among suppressions, difficulties, confiscations and returns, starting with the suppression laws promulgated in 1807 by Giuseppe Bonaparte, which upset the life of the monastery and made the archive state property (though still under the custody of the monks), a condition destined not to change even after the Restoration, when the property of the State over the Cassinese archive would be reconfirmed by the “organic law” on the Archives of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies of November 12, 1818, and the documentary heritage would go on to constitute a section of the Grande archivio (today the State Archive) of Naples.

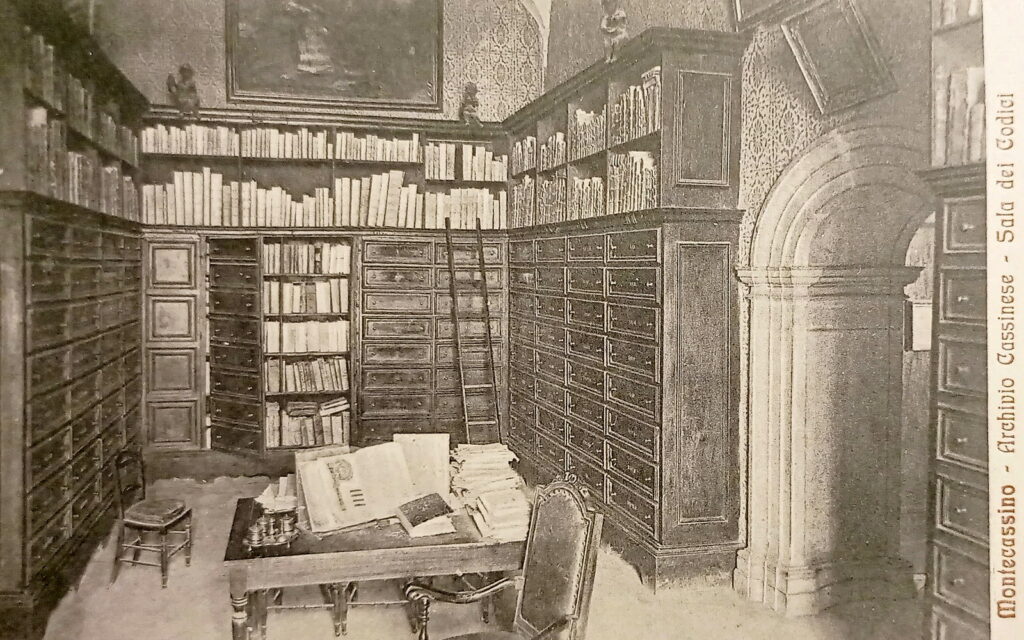

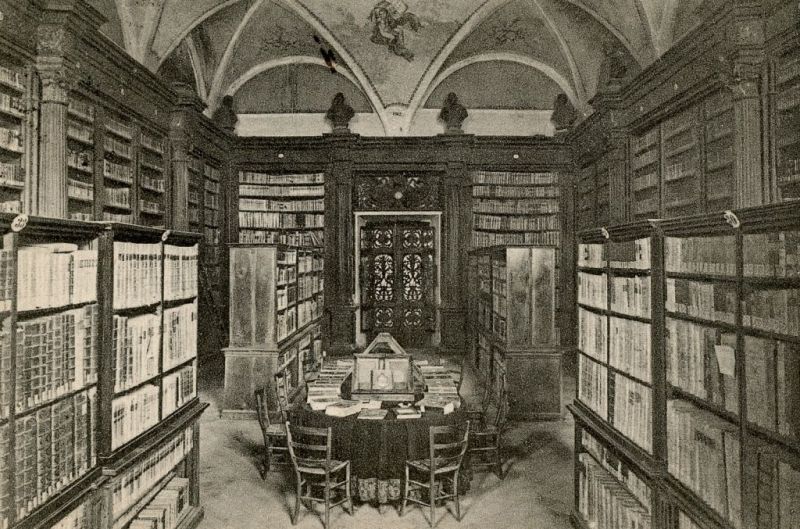

In the Introduction to the first volume of the Regesti Leccisotti also gives us an almost photographic image of the premises and layout of the archive, destined to remain more or less the same since 1631, when Abbot Angelo Grassi had premises built acconci ad rectius servanda archivi nostri veneranda monumenta.

The general arrangement, therefore, did not change until the time of the 1943 eviction, when under the watchful eye of archivist d. Mauro Inguanez, the documents, together with the library’s codices, were at first sheltered in the Rocca di Spoleto, and then again transported to Rome, where they arrived on December 8, 1943, to be delivered two days later to the Prefect of the Vatican Apostolic Library, Anselmo M. Albareda.

Pictures of the displacement and the redelivery ceremony can be seen below.

Before these events, the archive occupied three large ground-floor rooms located on the right-hand side with respect to the main entrance of the Abbey, at the ends of which there were, on one side, a small room where, on various shelves, miscellaneous materials were preserved, including the large collection of administrative books, and on the other, a large two-bay hall later used as a consultation room with the name Biblioteca Paolina, in honor of Paul the Deacon. The rooms were numbered in reverse order with respect to their position, and therefore the one closest to the entrance was Room III and the farthest was Room I.

At least until 1504, the primitive core of the archive was almost entirely preserved in the so-called Room II: later, when the two depositories of Room I and Room III were created, the former came to contain the paper documentation relating to ecclesiastical jurisdiction (Curia spirituale) and, in part, documents relating to the administration of goods, while the latter, in large cabinets, preserved the records of feudal jurisdiction (Curia temporale, that is, the government of the Cassinese State from the 16th century to the early 19th), and the rich collection of notarial protocols. In Room II, instead, it was preferred to preserve the unity of the oldest collection, also because it would not have been easy to separate the various documents: only later, from the material preserved in Room II, the so-called fondo diplomatico was constituted, transferring to Room I the documents of the priories and of administration, and to Room III the papal bulls and the diplomas.

The “tragic storm” of 1944, as Leccisotti called the disastrous bombing that almost entirely destroyed the Abbey, obviously also devastated the rooms of the archive: but the documents, previously evacuated elsewhere, were saved. Afterwards, with tenacity and patience, everything was rebuilt “as it was and where it was,” but during reconstruction some modifications were made to the structure of the Abbey, and so the layout of the archive also changed. First of all, the entrance door was moved near the porter’s lodge: thus Room III took the place of the ancient Room I, while Room I took the place of the ancient Room III, but the documentary material retained its previous arrangement. The codices were all moved to a smaller and dedicated room, Room IV, created within the ancient perimeter, while the Biblioteca Paolina, once reserved for consulting archival records due to its proximity to the storage rooms, was merged with other rooms to form a single library along with the other printed collections.

With the structure of the buildings rebuilt, in 1955 the collections could return from Rome to their original location and a monumental campaign of census, inventory, and regestation of the documents could begin, one that would finally provide scholars around the world with a reliable account of the immense Cassinese heritage: the archive could begin to breathe again with the Abbey.