A considerable part of Montecassino’s library holdings is written in a script characteristic of southern Italy: the Beneventan.

This particularly script is attested since the last decades of the 8th century. Its formation from the New Cursive of the Roman tradition came to fruition in the southern region of Lombard domination: the so-called Langobardia minor. Here, in fact, a separate and different written culture developed from the Carolingian one, and this is expression of the strong Lombard ethnic consciousness. The Lombard culture ended up coinciding with the Benedictine one, of which the monastery of Montecassino constituted one of the most prestigious centers.

1.1 Deployment area

The Beneventan script was employed not only in Langobardia minor in the strict sense, but in the whole area of Lombard culture in central and southern Italy, which had as its upper boundary an ideal line drawn from the Tyrrhenian to the Adriatic coast, from Rome to Ascoli Piceno. It included the Tyrrhenian coast itself, excluding the coastal duchies, and the Lombard principalities as far as the southern limits reached by their hegemony. Finally, it extended eastward, beyond the shores of the Adriatic, to the Tremiti islands and the Dalmatian coast, where the Beneventan script arrived thanks to trade relations with Apulian cities and the dependence from southern Italian abbeys of some important Dalmatian monasteries (e.g., St. Chrysogonus in Zadar).

1.2 Writing morphology

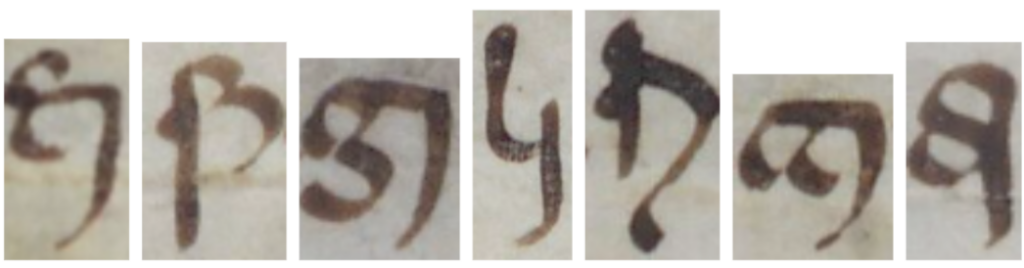

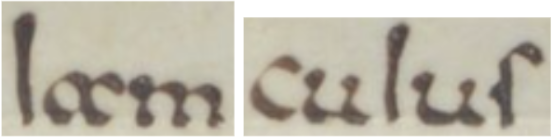

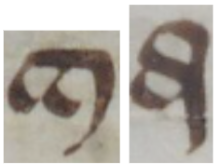

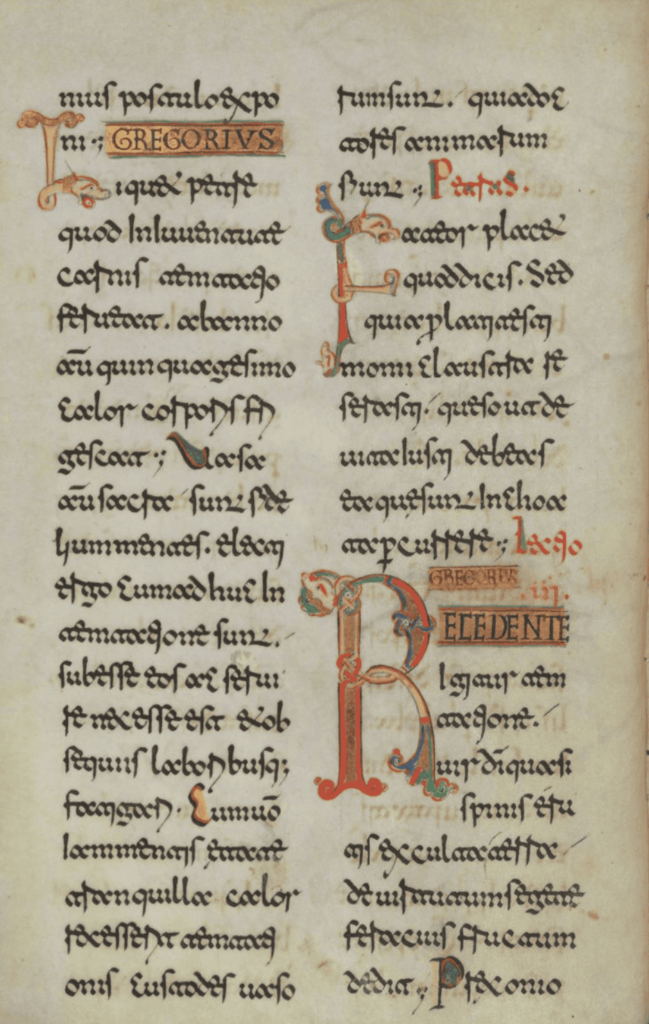

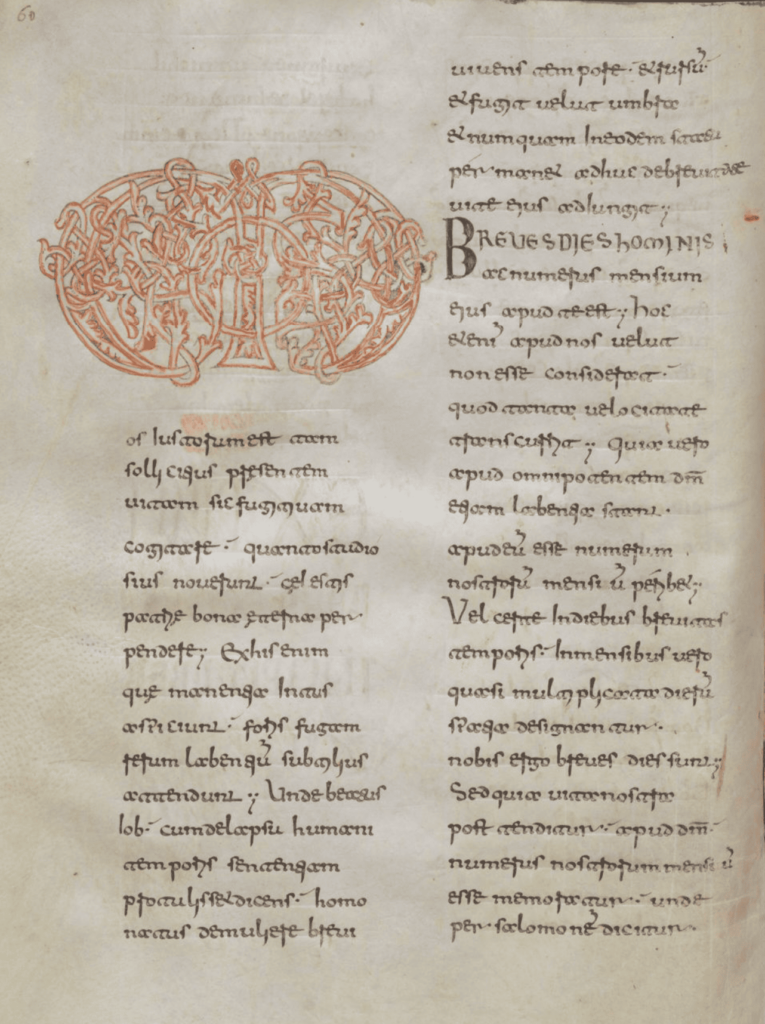

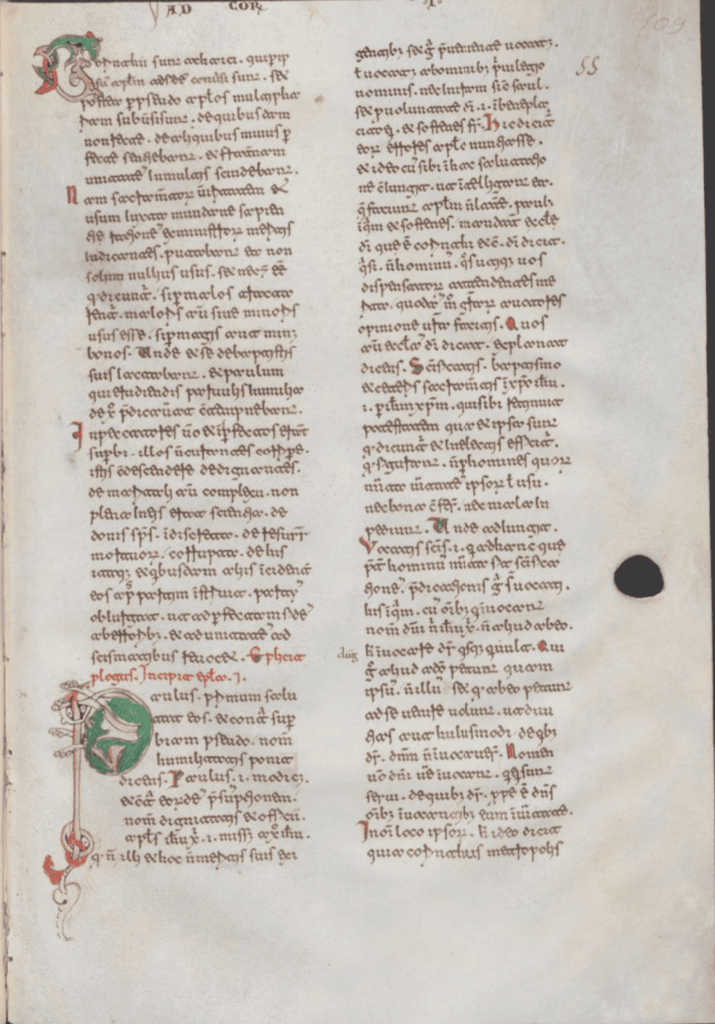

It was probably the need for a more agile and less demanding script than uncial and semiuncial that led to a calligraphy of the New Roman cursive, resulting in the development of the Beneventan minuscule.The distinctive characteristics of this writing were identified by Elias Avery Lowe in his monumental 1914 work, The Beneventan Script : here some specimens are offered lokking at Cod. 82:

– a resembling two juxtaposed c’s tending to touch at the top;

– t with loop to the left of the vertical stroke wide until it almost touches the writing line;

– mandatory ligature of i when it follows the letters e, f, g, l, r, t;

– use of the high I instead of the normal low i when the letter is at the beginning of word (In, Impar, Itinera), unless it is followed by letters that extend below or above the writing line(ibi, ille, ipse), and when it has a semivocalic function(Iam, eIus, IeIuniis);

– differentiation in the form of the ligature ti depending on whether the group expresses hard(tibi) or soft(pretium) sound.

1.3 Origin

In the aforementioned scientific work, Lowe inextricably identified the stages of the history of beneventan script with the history of the monastery of Montecassino. In this way Lowe has placed the attainment of the canon within the walls of the coenoby at the time of Abbot Desiderius (1058- 1087). In fact, as Guglielmo Cavallo noted in 1970(Structure and articulation of the beneventana minuscule book between the 10th- and 12th-centuries), since the canonization of a script is a unitary phenomenon, it requires a cultural and political unity that fosters this process: in the case of beneventan script, the former was ensured by the numerous Benedictine foundations that promoted Longobard-Cassinese culture; the latter was achieved after the mid-10th century with Pandolfo “Capodiferro” (943-981), who reunified all of Langobardia minor by extending his hegemony into the duchy of Spoleto and the marca of Camerino. The canonization of beneventan writing would thus have occurred around the third twenty-five years of the 10th century, not so much in Montecassino – which was still struggling to reorganize itself due to the destruction by the Saracens in 883 and the rebuilt in 950, – but rather in the city of Benevento ruled by Bishop Landulf I, elevated to archbishopric in 969.

1.4 Bari type and Cassinese type

By the 11th century, the Beneventan script diversified, roughly according to geographical areas, into the Bari and Cassinese types.

The former was defined in Bari at the beginning of the century, perhaps also under the influence of Byzantine models circulating in Apulian territory, such as the Perlschrift or the late capital (as Guglelmo Cavallo suggests in the above-mentioned contribution published in 1970). Its distinctive features are: thin, flowing and uniform hatching; tendency to bilinearism with strong reduction of ascending and descending rods; enlargement of letters’ cores; rounded forms. Its area of diffusion extended beyond the Land of Bari, stretching from the Apulian coast to Dalmatia.

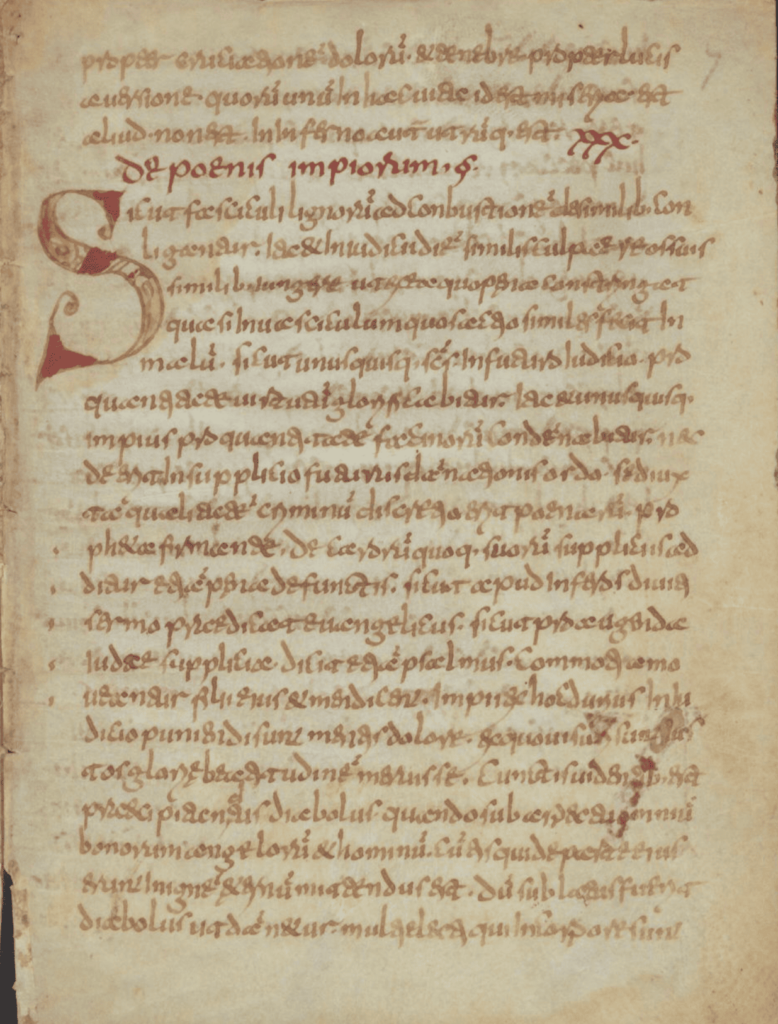

Cassinese typing, on the other hand, developed within the walls of the Benedictine coenoby of Montecassino, reaching perfection under abbots Desiderius (1058-1087) and Oderisius (1087-1105). During this phase (to which Francis Newton devoted a monumental monography in 1999, The scriptorium and library at Monte Cassino 1058-1105), the use of a soft-tipped, obliquely cut pen produced two peculiar effects on the writing employed

by the Cassinese scribes: the first is the breaking up of the short vertical strokes of the letters that are formed on the model of the i (thus m, n, u and the second of h) and is manifested by an overlapping lozenge pattern; the second is the perfect alignment of the horizontal strokes of some letters ( e, f, g, r, t), with the consequence that the words appear to hang along a rope. As with the Bari type, the area of dissemination of the Cassinese beneventan extended far beyond the Benedictine monastery, eventually involving almost all of Lombard southern Italy.

1.5 Decay of the beneventan script

Beginning in the 12th century, there was the establishment of the all vectors of the new Carolingian culture: the final advent of the Normans in southern Italy, the political gravitation of Montecassino toward them and Rome, the founding of new Cistercian monasteries, and the introduction of graphic and textual models from other regions. All these elements resulted in the end of Longobard tradition and, with it, the writing that had been the expression and mean of transmission of culture. From that time on, the beneventan script began to manifest more and more the introduction of elements foreign to the traditional graphic type, until it was replaced altogether by late Caroline and Gothic. However, in some centers where it was deeply rooted, above all Montecassino, it continued to be employed for a long time to come in artificial forms. For example, in the second half of the 12th century the manuscripts Montecassino, Biblioteca Statale del Monumento Nazionale, Archivio, Cod. 235 was set up in the Benedictine monastery: this is the only witness of the Pauline Epistles with commentary by Gilbert Porretan and the only glossed Bible codex in Beneventan script preserved at Montecassino, .

Representative manuscripts

(10th cent. ex.-XI in., untyped beneventana)

f. 55r

(12th century2, final phase of the beneventana)