1. The scriptorium in the Middle Ages

The Abbey of Monte Cassino was one of Europe’s most important workplace for production and preservation of books. From its origins manuscripts and reading activity appear, in fact, as a part of the monastic life, as witnessed by the Regula of its founder St. Benedict. The monks were required to read and get educated both in common and in private life, observing strict precepts that included reading and study among their daily activities.

The current idea of culture was unkonwn to Benedict’s perspective, as to early monasticism: reading, prescribed by the Regula, had as its object the Holy Scriptures, the works of the Fathers, and texts aimed at worship and personal prayer. In the early Middle Ages books and writing became instruments through which the monastic school take the place of the late antique school; furthermore the copying of manuscripts became an activity consecrated to the Lord for the expiation of sins and the salvation of the soul. The care and preservation of books was born from these dynamics. Since the late period of 8th century, the first manuscripts produced at Montecassino are expression of a culture anchored in the Rugula, focused on teaching and practical needs of the monks. At that time Paulus Diaconus, (Cividale del Friuli 720 – Montecassino 799), monk, historian and author of the Historia Langobardorum, educated at the Lombard court of Pavia, plays an essential role in scholastic organization, book manufacturing and library growth. The beginning of a new phase for the scriptorium is marked, however, by the return of the monks to the Holy Mountain, after the Capuan period from 883 to 950. Book production was stylistically uncertain, but quantitatively substantial and widespread throughout the Abbey’s dependencies, even beyond the borders of the territory. The library heritage of previous eras is consciously revisited, in order to create new textual, graphic, and artistic types.

2. Theobaldian and Desirean ages

The great abbots of the 11th century, Theobaldus (1022-1035) and especially Desiderius (1058-1087), contributed to enhance the golden age of Monte Cassino: both of them engaged an intense activity in construction, acquisition of liturgical furnishings, and book production. The age of Abbot Desiderius, who later became pope Victor III, is the apex of manuscritps’ copying at the Benedictine monastery. During his abbacy, the basilica was rebuilt in only 5 years (1066-1071), and the monastery was enriched with mosaics, enamels, and liturgical goldworks, testifying the importance of Byzantine influences in the formative process of the local craftsmen. Architectural patronage was accompanied by book patronage: these years were essential for the scriptorium, with the fine-tuning of beneventan script in its classical form and the setting up of about 70 manuscripts, many of them magnificently illuminated. The power of Montecassino did not come to a stop at the end of Desiderius’s golden age, and his immediate successor Oderisius, who died in 1105. Nevertheless, between the end of the 11th century and the first half of the 12th century, the slow political decline of the Abbey began: Montecassino territory found itself embroiled in the struggles between the papacy and the Normans and in the Anacletian schism (1130). These events provoked the loss of the Abbey’s long-standing autonomy, with negative repercussions on its artistic and cultural existence. Despite this, the scriptorium‘s activity did not cease in the 12th and 13th centuries, although the history of its book production has often been unjustly neglected: scholars have deemed these centuries as a phase of stagnation, in which the manuscritps’ copying and decorating wearily re-proposes models of the desiderian Initialornamentik, even if these models were performed in an increasingly unsupervised way. On the contrary, recent studies are showing how the Abbey’s scriptorium opened itself to influences from outside, while it was strongly anchored in local tradition of copying and decoration of texts. In particular, the 12th century is a time of great change and transformation for Montecassino: as it is witnessed by the establishment of a new script, the Caroline.

3. The scriptorium in the Renaissance and the sixteenth century.

However, the Abbey experiences a period of profound decline, due to the loss of autonomy, wars, and its becoming a pawn in the power games of Renaissance Italy.

The commissioning of manuscripts is central to the religious context of the sixteenth century, emphasizing the perfection and sumptuousness of books’ codicological, paleographic and decorative apparatuses, and it is aimed at promoting the role of Montecassino as the center and guide of the Italian Benedictine world, in the wake of a tradition that continues beyond the bounders of the Middle Ages.

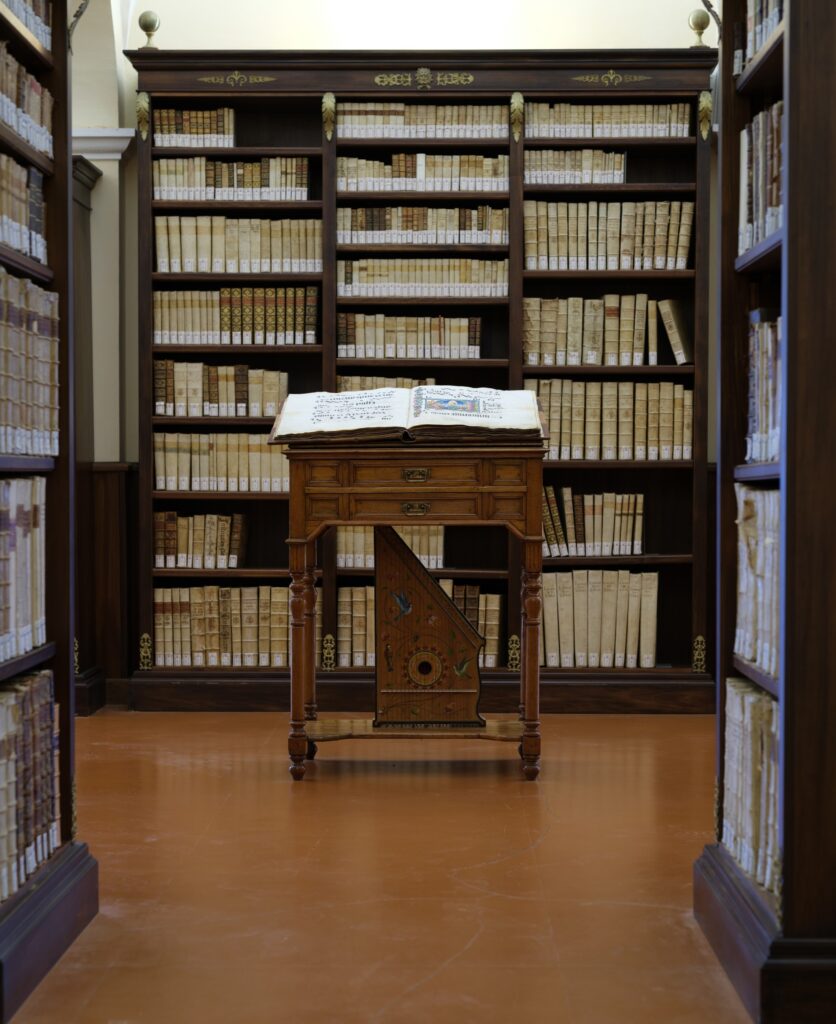

4. Montecassino at the present time

Montecassino is one of the rare examples of a medieval monastery that still preserves a substantial heritage of manuscripts produced in its own scriptorium or acquired from outside. Such books are the almost unique evidence of the ancient splendor of the Abbey. Other artistic evidenceses have disappeared or survived in fragmentary form, which in turn can be reconstructed mainly, and only minimally, through the indirect memory of written sources. Over the centuries, the Benedictine monastery played a central role in the transmission of ancient and medieval texts, the success of a specific script (the Beneventan minuscule ‘cassinese’), the development of an original decorative tradition, and the refinement and reinterpretation of peculiar book types.